Designing with wellbeing in mind

Thoughtful architecture has the ability to influence how we experience daily life. It shapes how people feel, think, and connect - beyond aesthetics and functionality.

We’ve been investigating places that promote wellbeing. In particular, we’ve been looking at how biophilic principles and thoughtful design choices can support both physical and mental health, foster a sense of belonging, and create meaningful connections between people and place.

We explored projects across sectors and continents, each offering a distinct perspective on how architecture can shape healthier, more connected, more human experiences. From biophilic homes to community-driven healthcare environments, here are the projects that sparked our conversations.

Across many cultural contexts, the presence of nature consistently improves how a place feels. Whether through materiality, views, ventilation or greenery, these elements help regulate stress, create moments of calm and support a more intuitive relationship with the environment. Saoir House by Refresh Design uses natural materials, open volumes and indoor-outdoor thresholds to create spaces that feel warm and breathable, showing how biophilic design principles can be embedded in structure, not added later.

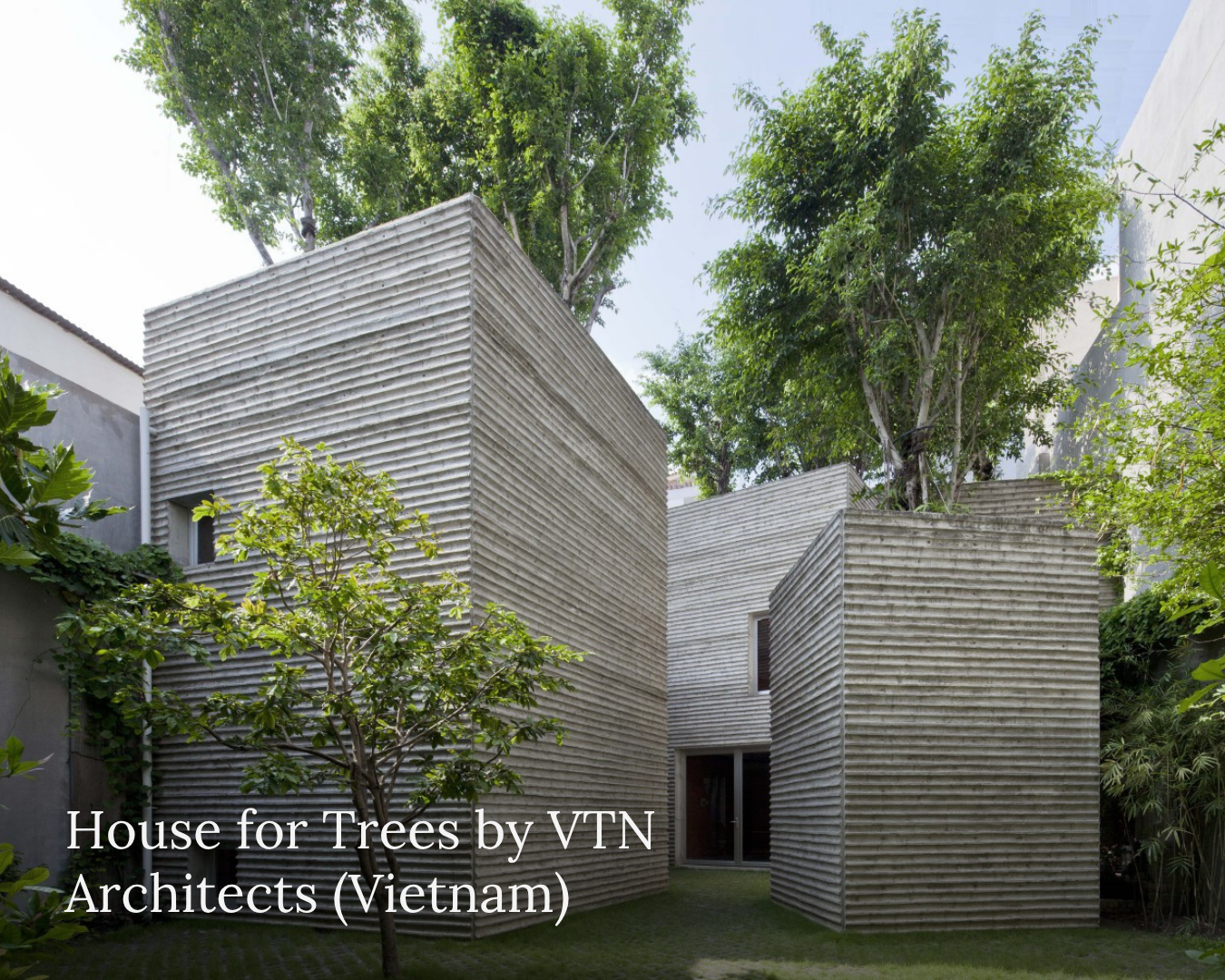

At 25 King Street, exposed CLT, generous daylight and natural ventilation demonstrate how workplaces benefit from biophilic approaches as much as homes do, while House for Trees in Ho Chi Minh City reintroduces green space into a dense neighbourhood. Multi-level planting and rooftop gardens bring daylight, shade and natural ventilation back into daily life, offering a restorative contrast to the surrounding urban fabric.

Wellbeing is strengthened when architecture supports social connection. Spaces that feel welcoming and familiar tend to reduce anxiety, encourage participation and create a sense of shared ownership.

At Maggie’s Yorkshire, Heatherwick Studio shaped a series of garden pods that feel grounded and nurturing. The pods are designed to support emotional and physical wellbeing, and the landscape becomes part of the experience – something people can see, walk through, and engage with. The space offers respite from the everyday clinical environment to cancer patients and visitors. Similarly, the Queensland Children’s Hospital incorporates rooftop gardens, non-clinical activity spaces and a tree-inspired façade to create uplifting environments for children, families and staff.

At Singapore’s Garden Waterfront development, play, movement and gathering spaces are integrated into a dense residential precinct. Playgrounds, fitness stations, rooftop gardens and hawker centres form part of everyday routines, creating a neighbourhood shaped around wellbeing.

The Dakabin State High School Health Hub brings mental and physical health support services into a domestic environment. Set on a high-school site and designed with student input, the space looks and feels like a home. Small nooks, kitchen spaces and soft finishes create settings that feel approachable, reducing the formality often associated with health facilities, and fostering a sense of comfort and community for its young users.

Shared spaces hold significant influence over how people use a building. When circulation routes, communal areas and gathering spaces are well-considered, they encourage interaction and support a sense of community. Norway’s Horten Videregående Skole uses natural materials and well-proportioned shared spaces to support collaboration and comfort in a secondary school setting, marrying aesthetic considerations with functional requirements.

In Commerzbank Tower, the world’s first ecological office tower, biophilic design principles are used to blend sustainability and wellbeing. It provides breathing room amidst the corporate hustle through its triangular layout, revolving sky gardens, and natural ventilation woven throughout. Each office is daylit by adjustable windows for personalised environmental management and comfort.

The Translational Research Institute (TRI) makes use of a central courtyard and thoughtfully positioned "bubbles" to promotes interaction between four connected institutions. The line between the lab and life is blurred by gardens and natural light – where individuals feel rooted, connected, and well, innovation flourishes.

Wellbeing is closely tied to environmental quality – air movement, temperature, shade, acoustics and access to landscape. When buildings use climate-responsive strategies, people often feel the benefits immediately: cooler microclimates, quieter spaces, and more comfortable interiors. Singapore’s Khoo Teck Puat Hospital demonstrates this connection at a city scale.

The hospital integrates natural ventilation, stormwater cooling and layered landscaping to create a healthcare environment that feels fresh, shaded and deeply connected to place. Public gardens extend the hospital’s impact into the community, making it a social as well as clinical asset.

Wellbeing should be approached not as a singular gesture, but as a combination of small, thoughtful decisions. Materials, planting, circulation, climate strategies, shared spaces and domestic-scale details all contribute to environments that feel grounded and supportive.

These insights continue to shape how we think about wellbeing within our own work –responding to context, community and the everyday rhythms of the people who use these spaces.

When we place wellbeing at the centre of the design process, we shape environments that feel intuitive, supportive and calm. It’s not about creating perfect conditions, but about making thoughtful decisions that improve everyday experience.